Last (Australian) summer I got completely spooked by reading an apocalyptic novel – Leave the World Behind – by Rumaan Alam. Not my usual literary genre of choice, I had picked it up at my brother’s holiday house and couldn’t stop reading. It’s the story of a mysterious blackout along the East Coast of America and the collapse of civilisation. After finishing it I had a sleepless night worrying about the state of the world – everything from climate change, wars, plastics in the environment (and our bodies) to Trump getting back into the White House and AI into the wrong hands.

For me one of the best antidotes to Weltangst and negativity is engaging in the arts. The arts connect us to joy, inspiration, beauty, creativity and to one another, expand our understanding of the world and humanity, enable us to dream and soar above the everyday – even if fleetingly. We may laugh, we may cry or be filled with awe and wonder. The arts can also shock, provoke and act as a call to action.

During the endless Melbourne COVID lockdowns, tapping into all the wonderful plays, operas and musicals streamed free from the world’s stages was a silver lining. It also gave me hope and restored my faith in humanity, which was challenged by all the fear-mongering and survival of the fittest behaviours – remember the loo paper hoarding?!

An emerging body of research, strengthened since COVID, highlights the link between engaging/participating in the arts and mental health benefits. It makes it all the more regrettable that public arts funding gets slashed during periods of economic downturn. The cultural sector in the UK, for example, is suffering huge cuts. Interestingly – according to my research – Finland has the highest per capita public arts spending, and is also the country that ranks highest in the UN World Happiness Report – I rest my case.

There’s also opportunity for arts to inform and be integrated into social policy. A good example of how this can work in action is Streetwise Opera, a UK charity that connects those living with homelessness with world-class artists to co-create bold new works, bringing together diverse voices and stories, improving the wellbeing, confidence and social connectedness of participants. It’s a great example of how an otherwise elite art form can be reinterpreted for social good. See: https://streetwiseopera.org/

Another immersive, affordable and accessible way to experience the arts across multiple genres is to attend a Fringe Festival. In 2019 I happened to visit Avignon during the Avignon Festival in July and was drawn to Avignon Le Off (their name for the Fringe). I dashed around seeing French theatre (dusting off my A’level French), watching a naked yoga dance (which was rather beautiful and not remotely salacious), a clown-like comedy set in a barber’s shop, and a brilliant and hugely powerful two-person play written and performed by Tim Marriott (of Brittas Empire fame) about Mengele meeting the angel of death on a Brazilian beach. And everywhere I turned there was this artsy soup of drag queens, artists riding unicycles, singers, street artists and acrobats. Some of the works I saw there happened to be Adelaide Fringe shows. And in the magical way the universe works, a year later I ended up doing grant-seeking and advisory work for them.

Fast forward a few years to August 2023, and I met a colleague from the Adelaide Fringe in Edinburgh when the Festival and Fringe were in full flow. Of course, Edinburgh is where the Fringe movement was born in 1947, when eight theatre groups turned up uninvited to perform at the Edinburgh International Festival.

While I mainly focussed on Fringe shows, I also attended a couple of Festival events. A standout was a chat between Iván Fischer, Director of the Budapest Festival Orchestra (BFO), and Edinburgh Festival Director, Nicola Benedetti, in the Usher Hall. We – the audience – lay or sat on the floor on bean bags and heard Fischer talk about – and demonstrate – how an orchestra can maintain contemporary relevance away from the formal staging of a classical concert. Many of the musicians in the BFO play other forms of music, and we heard a selection: Monteverdi madrigals (with instrumentalists singing in the chorus), Argentinian Tango, Klezmer music and rousing wedding music from Transylvania. An absolute treat.

Other favourites were a one-man play, In Loyal Company, a true story of missing WWII soldier Arthur Robinson, written and performed by his great-nephew David William Bryan. A hugely energetic, visceral and totally captivating performance, you’re on board his ship in Singapore when it gets bombed, you sweat and shiver through dysentery in Malaya, and feel gutted when he finally returns to Liverpool after the war to find life has moved on in his absence. Another very poignant play – Shanti and Naz –was about two best friends, one Hindu and one Sikh, during the time of partition in India. By complete contrast A Migrant’s Son (an Adelaide Fringe production) presents a true-life story of the Greek migrant experience to Australia. It’s a musical journey created and sung by Michaela Burger and is full of humour, heart and a few horrors along the way. Burger has a fabulous voice and was joined by a community choir as the chorus.

The New Revue was a sharp satire on (mainly British) current affairs which back then featured Rishi Sunak, BoJo, Keir Starmer, Suella Braverman and Paddington Bear. How fortunate are those of us who live in democratic societies and enjoy freedom of speech and self-expression. A healthy and vibrant arts scene encourages the exchange of ideas, the exploration of stories and different art forms. There are all too many examples past and present of autocratic regimes suppressing the arts and subverting them for state propaganda.

I loved being in Edinburgh: the buzz and festival vibe; the many tartan and shortbread shops; the whisky; people-watching; pop-up shows and street artists; bagpipes; summer chill and cloud; ancient stone and cobbles; and, towering over it all, the great bastion of the castle. I reconnected with friends I hadn’t seen for many years and stayed in their delightfully rambling house in Morningside. I also stayed with Australian friends in the Borders, and probably drove them mad running around to so many shows.

I did the same thing in Adelaide in February, partly as my clients at Adelaide Fringe generously gave me a bunch of comp tickets and also because it was Writers’ Week. I ran between the two – literally!

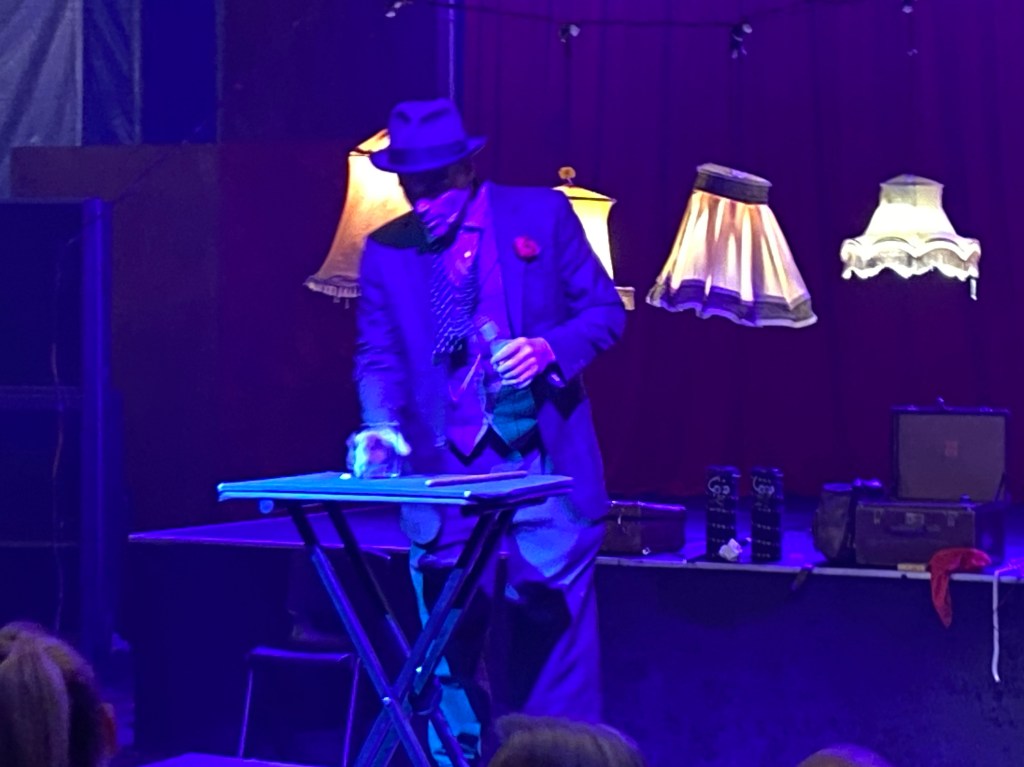

Highlights included a magic show, Charlie Caper, how DID he do it? I strained to see the tricks and shortcuts but couldn’t. I loved the show and the old world feel conjured up (haha!) by his Fedora, three-piece suit, bow tie and the tasselled lamps. A stand-up comedy session in a converted railway carriage was raw and vulnerable while a Japanese circus, YOAH, was highly stylised and silent – all black and white and techno. Lolly Bag, a one-woman show by the talented Hannah Camilleri was a delight. Very quick, very original, and very funny, she played a whole a range of characters from a curmudgeonly car mechanic to a frazzled Year 8 class teacher, mixing improv and audience participation to great effect.

I also had the pleasure of seeing two more Tim Marriott plays – we have stayed in touch since I got chatting to him, his wife and dogs in Avignon. Appraisal was a gripping all-too-realistic and, in parts, darkly funny, two-person play about a toxic work culture, the abuse of power and position. Watson, The Final Problem is based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. With Big Ben chiming in the background and a Victorian-era room complete with hat stand, wooden chest, chair, desk and diary, we were transported to London, where Dr Watson looks back on his life and friendship with Sherlock Holmes. Tim Marriott’s masterful monologue took us on a rollercoaster ride culminating in the final demise of the detective at the hands of Moriarty at the Reichenbach Falls.

Cramming in – you know me – Writer’s Week events, it was a delight listening to Irish writer Anne Enright talking about families, Irish mothers and poets in relation to her new book The Wren, The Wren, and hearing what broadcasters Leigh Sales and Lisa Miller had to say about storytelling. I also attended an event at the Town Hall, where a group of writers each read a piece about family. My absolute favourite was by Martin Flanagan.

On this 66th birthday he went back where he was born, the Queen Victoria hospital in Tasmania (now offices), to write a letter to his late mother. Warm, moving, fond and funny, it was clearly part of an ongoing conversation with her. He recalled his friend Michael Long saying: “the silliest thing white fellas say is that you can’t talk to the dead.” Michael, whose mother died with he was 13, has a cup of tea with his mother every day. Martin concluded his birthplace reflection by saying to his mother: “I knew I’d find you here.” I found an extract from this tribute online if you’d like to read more. Go to: https://footyology.com.au/martin-flanagan-talking-to-mum/

That’s what I love about the arts, it all comes down to storytelling in one form or another: . “You’re never going to kill storytelling, because it’s built in the human plan. We come with it.” – Margaret Atwood,