Located in Minster Yard just behind York Minster is Treasurer’s House, a dwelling with a multi-layered history. Situated over a Roman road, the original house was built for the first Treasurer of York Minster in 1091 and remained the Treasurer’s House until the Reformation.

Over the centuries changes and additions were made to the building and in the 18th century it was divided into several residences, much of it falling into disrepair. Frank Green, a bachelor and wealthy industrialist, bought and restored each part of the house between 1897 and 1898, creating a town house as a showcase for his collection of antique furniture, paintings and objets d’art. And it’s been immaculately preserved.

Green donated the house and his collection to the National Trust in 1930 – it was the first historic house acquired by the Trust with its contents complete. One of his stipulations was that visits to the house should be by guided tour only. His aim was for the house to be maintained exactly as he intended – he was a very exacting man with an obsession for tidiness – but he wanted people to enjoy and appreciate the house as he left it. Green threatened to return to haunt the house if his wishes were not respected creating the prospect of additional spectral sightings. Several ghosts are reputed to haunt the house – from Green himself to a lady in grey and shield-bearing Roman legionaries in green tunics in the cellar!

Frank Green’s restored Jacobean townhouse has thirteen period rooms, all representing a different style or era, which I found to be a bit of a mishmash. And while there are some very significant and noteworthy pieces, it’s quite an ad hoc collection and there are not many valuable paintings bar a painting by 16th century Dutch painter Joachim Beuckelaer in the grand hall. However, the house breathes the ethos of its owner, the character of the man as interesting as his collection.

Frank Green was the son of Sir Edward Green, 1st Baronet and a Yorkshire industrialist. In those days there was a clear divide between being born into wealth and those who made their money from industry. Frank’s wealth came from the family business – his grandfather invented the ‘economiser’ a device that improved the efficiency of hot water boilers. The Green family were keen on horses and hunting and there’s a picture in one of the rooms of Frank Green in Hunting Pink – he was Master of the York and Ainsty Hounds. Clearly fashion-conscious – he favoured floppy bow ties and changed his clothes three times a day – and possibly vain to boot, there’s a picture of him wearing morning trousers with a pleat on the outside, following a trend – trumpeted as ‘sartorial innovation’ – set by King George V at Ascot Races in 1922.

He was keen on royal connections and hobnobbing. in June 1900 Edward VII and Queen Alexandra visited as Prince and Princess of Wales along with their daughter Victoria. It was in their honour that the King’s Room, Queen’s Room and Princess Victoria’s Room were so named.

The drawing room is furnished as a formal salon in the Versailles style with chandelier candelabras, mirrors, gilt wood furniture and marquetry. The top of a marquetry kneehole desk dating from 1710 is made of brass inlaid in tortoiseshell and depicts scenes from a performance of the Comédie-Italienne.

The furniture in this room is stapled to the ground to prevent it being moved or re-arranged. He had no tolerance for “mess and muddle”, wanted everything in its place and instructions dotted around the house indicate he was quite the stickler – from requiring workers to wear slippers to having pieces of coal wrapped in newspaper to prevent unnecessary noise. A former kitchen maid related how Frank would inspect the kitchen, turning out any drawers he thought were untidy.

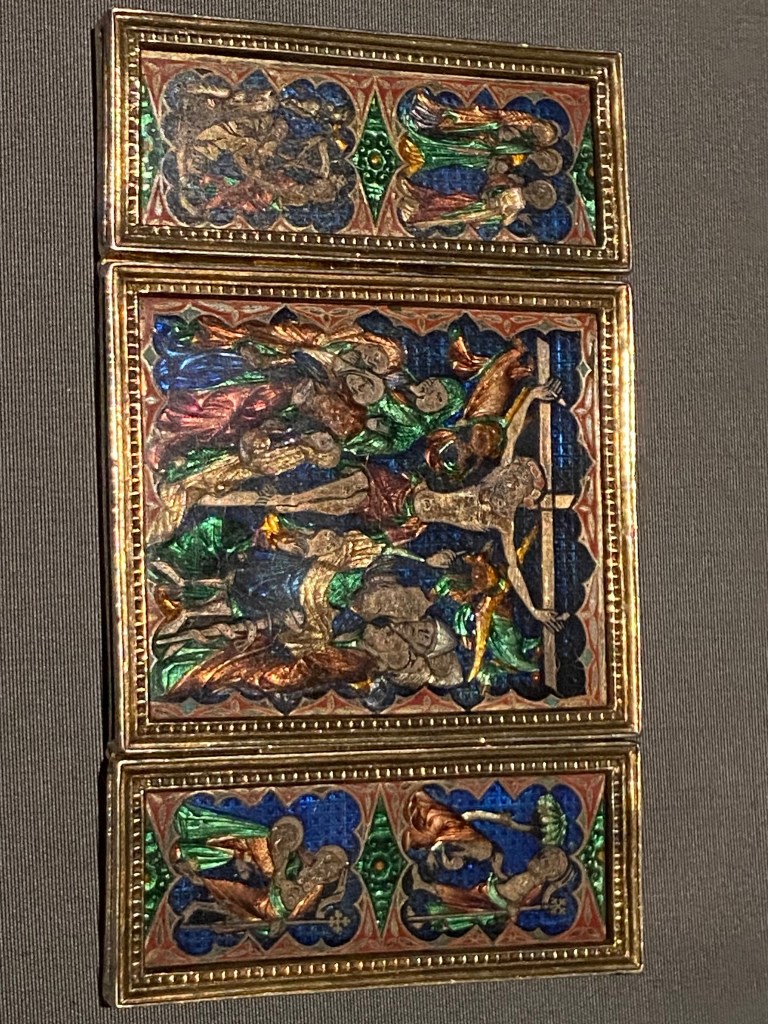

In his free time, he travelled around Europe in one of his Rolls-Royce cars seeking and purchasing items for his collection. Three of his collectibles that I found of particular interest were a witch ball, a French Boulle clock (made around 1720) and a Queen Anne tapestry bed cover. In the 17th and 18th centuries witch balls were made of glass and hung by windows to ward off evil spirits. The thinking was that witches would be scared off by seeing their own reflections. The belief that witches had the power to inflict death or illness simply by looking at a person or animal was widespread at the time.

The Boulle clock is an ornate Rococo piece with a calendar dial on the left and a lunar dial on the right. The calendar dial has 31 numbers around the circumference, the months of the year in French and the signs of the Zodiac, and the lunar calendar has the age of the moon in Arabic numbers and 24-hour tidal dial of the river Seine.

The Queen Anne period bedspread is displayed in the King’s Room, and the design includes a cornucopia representing fertility with pomegranate seeds on the male side (right) and a rose on the female side. The Tapestry Room is lined with oak panelled walls and hung with Flemish tapestries from the 17th Century known as ‘stumpwork’, a form of raised embroidery. And a tapestry chair – associated with a ghost sighting – reminds us who is in charge – Please do not sit – by order of Frank Green.

One of the most over-the-top features of the house is the medieval banqueting hall. The half-timbered gallery was created by removing the first floor above to open up the space. Complete with fireplace, minstrel’s gallery, stag’s horns and a massive polished oak refectory table from the 1600s, the great hall looks somewhat out of place in a town house!

Another way he created a stately home-type of environment was by buying up family portraits – some of these line the grand William and Mary-style staircase – in house sales following the tax hikes and high death duties following the First World War when there was a massive shift in land, goods and property by cash-strapped aristocrats.

I went down to the Treasurer’s House café at lunchtime and chose a cuppa and a gluten-free scone, which arrived fresh from the microwave blown up in its plastic wrap like a puffer fish until I popped it with a fork! I had to pay extra for cream and jam, a good investment as the scone needed a bit of love…

I had planned to do a tour of the Minster but didn’t have enough time to do justice to the £20 entry ticket – and that’s because I wasted time ploughing through racks of crappy clothes – a symphony of largely synthetic fabrics – in Marks & Spencer in the afternoon. I am told that quality M & S clothes are still available online or in bigger stores, but all was not lost as I bought some tights and a couple of cotton tops.

And, a silver lining, I stopped for a quick cup of tea in the M & S café, which had fantastic views back over towards the minster. And I just made it – at a sprint – to the Minster in time for evening prayer (there’s no choral evensong on Mondays) at 5.30pm.

Evensong or prayer is held in the Quire in the eastern part of the cathedral which has seating for clergy and the choir and houses the high altar. Going through the archway leading into the Quire with its gilded and painted ceiling bosses (recreations of the 15th-century originals following a fire in 1829) with views over to the great East Window, the largest expanse of medieval glass in the country, was a humbling moment. Note to self: next time I must do a tour of this magnificent place of worship dating back to the 13th century.