How often in life do we get the opportunity to reminisce about something from our childhood and then to step back into that treasured memory and find it still exists in time and place?

This was my experience at the Castle Museum in York. When planning my trip I remembered being enchanted, probably aged around ten or so, by Kirkgate, the museum’s recreation of a Victorian Street. I was thrilled to discover it’s still there; and not only still there but significantly enhanced after a major restoration in 2012.

The museum is housed in what was formerly the female prison, situated in the Norman Castle complex, and is located directly opposite Clifford’s Tower, the largest surviving part of York Castle, northern England’s greatest medieval fortress.

The Castle Museum was founded in 1938 by Dr Kirk, a practising medic who lived in nearby Pickering. Some of his patients were unable to pay his fees and so he would accept an ornament or object of interest in lieu of payment leading some people to hide their family heirlooms before one of his visits! By the 1930s he needed somewhere to display his extensive collection and the idea for the museum was born. The Castle Museum was the first in Britain to have room and street recreations rather than just display cabinets.

What I remembered most vividly was a carriage, coachman and (very) lifelike model horse. Looking down on Kirkgate from an upper level of the museum, I spotted the very same hansom cab, horse and coachman that I had seen in the 1970s. Thrilled to find it still there, I was off to a good start! Not only that but I discovered that the carriage – like most of the other items in the street – the lampposts, horse troughs and shopfronts are nearly all originals.

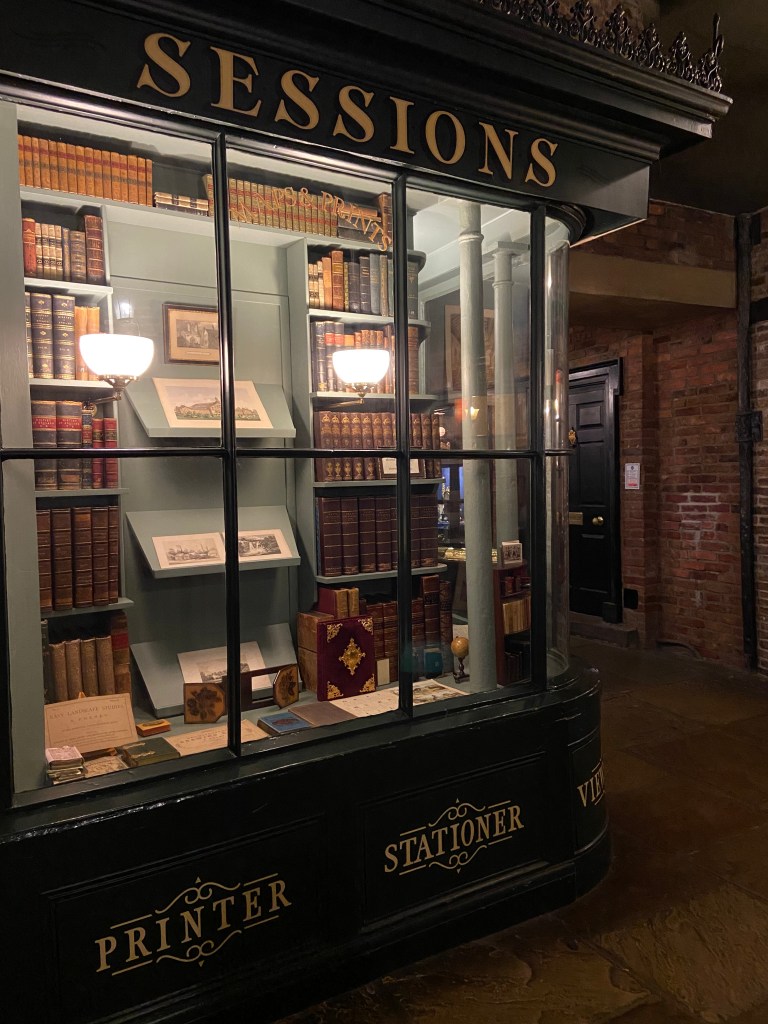

When Kirkgate was restored, the focus shifted to the later years of the Victorian era – 1870 to 1901, and the attention to detail is meticulous – the cobblestones, soundtrack of clopping horses, the dim Dickensian lighting, the buildings and the presentation of the shopfronts – each shop and business is named after a real business that operated in late Victorian York. There’s Horsleys, Gunsmiths, George Britton Grocers and importers of fine tea and coffee (such as Liptons), J W Nelson, Saddler, G E Barton confectioner, named after a Victorian confectioner and baker, Saville’s pharmacy and Leak and Thorp Drapers shop. Sessions Printers with its beautiful display of leather-bounds books and historic prints is still in operation today!

A coffin-makers shop displays handmade wooden coffins, an advert for Keen’s Mustard propped against one wall and a reminder that life is short – tempus fugit – hanging beside the desk, alongside chisels, hammers, brass plaques and handles. Similarly, next to the clockmaker’s is a studio with all the tools of the trade laid out on a bench.

I marvelled at the bolts of cloth at the drapers; the dress pattern, the fans and a poster advertising corsets – “Ensure a Graceful and Elegant Figure”. Reading Ruth Goodman’s How to be a Victorian, I learnt that corset-wearing was a mark of social respectability and corsets were deemed to protect a woman’s delicate internal organs, and to keep them warm. Corsets, properly worn, were thought to promote a whole range of health benefits including good posture. Being encased in a corset, ribs compressed, swathed in layers of petticoats and skirts and then caged in by a crinoline, forcing you to perch on the edge of your chair to do your needlework, must have been very restricting and uncomfortable! These were the days when women were considered the weaker sex – physically, intellectually and emotionally. Did you know that The Great Reform Act of 1832 excluded women from the electorate by defining voters as ‘male persons’? It wasn’t until 1928 that gender equality in voting was achieved.

There’s even a ‘second-hand’ shop in Kirkgate with a sign in the window requesting “left-off” clothing. The Victorians were recyclers and upcyclers – fabric costs were high and many families lived in poverty. Garments were “turned” with the outside becoming the inside to make them last longer or were remade and reworked to adapt to changing fashions.

The pharmacy was another source of fascination with its panelled wooden shelves lined with glass jars, canisters and curiously named perfumes such as Rough and Ready and Jockey Club Bouquet. Saville’s Golden liver and stomach mixture seems to have been a bit of a cure-all, treating “costiveness and disorders of the stomach and bowel, giddiness, pains in the head and cutaneous eruptions.” Although germ theory was gaining traction from the 1860s onwards, in the early part of Victoria’s reign disease was believed to be carried out in evil miasmas in the air, requiring poisons, waste matter and the noxious substances of disease to be expelled from the body. Bloodletting, leaches, lancing and purging were all in vogue and, in the absence of affordable doctors, housewives would often have a stock of drugs at home – many marketed with far-fetched claims, the pharmacy industry lacking any regulation. Beecham’s pills, for example, were made from aloes, ginger and soap – nothing to harm you, but nothing to heal you either. Other preparations contained opiates such as laudanum and there was widespread use of laxatives – senna, Epsom salts, syrup of figs and castor oil.

An electric hairbrush is advertised as strengthening hair, preventing baldness and relieving headaches in five minutes. If you Google head-massagers, you’ll see the Victorians were ahead of their time! When it comes to health and wellness, you could argue not much has changed in this respect: we still hanker after miracle cures and are vulnerable to marketing claims. And headaches and digestive problems are still very common – check out the shelves at any pharmacy!

Some of the facades, whether a business or a private residence, have fire plaques indicating the owner had taken out insurance, which entitled them to receive priority treatment. This was a time of marked social division, poverty, child labour, hunger, disease, overcrowded housing and overwork. A guide dressed in Victorian garb told us that the Rowntree Report, published in 1901, revealed that 27% of the population in York were living in insanitary conditions with one drop toilet to 52 people – a grim thought given the obsession with laxatives and bowel function!

The advent of the railways transformed York – in 1877 it boasted the largest station in the world – supporting tourism, communications and the confectionary industry. The railways also lead to the standardisation of time across Britain, replacing local time in different cities. The clock on the wall in Kirkgate would have been on Greenwich Mean Time, adopted in 1880.

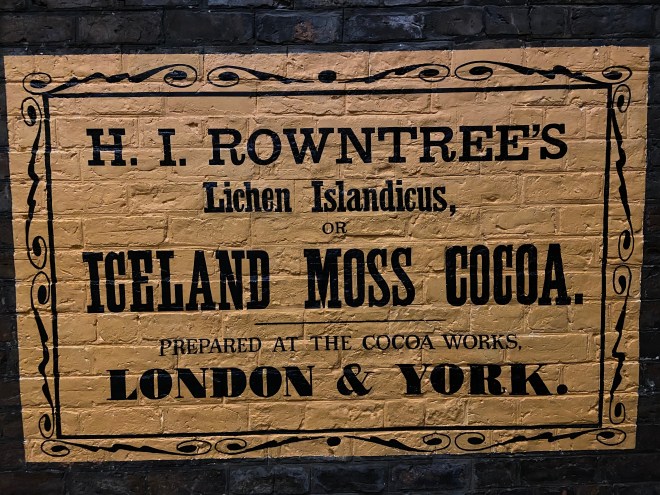

Rowntree, a Quaker company with a social and ethical conscience was founded in York in the 1860s. Making chocolates and later fruit pastilles, Rowntree’s were enlightened employers provided affordable housing and medical care for their workers. There’s a Temperance Cocoa Room in Kirkgate – the Rowntree family, like many Quakers, attributed many of society’s problems to alcohol and encouraged people to avoid the temptations of alcohol by drinking cocoa instead. What would they make of Baileys Chocolate Liqueur? An aberration that would no doubt make them turn in their graves!

Talking of turning in graves, my next blog will be on Treasury House in York, a house built directly over one of the Roman roads that led northwards out of York. Several ghosts are reputed to haunt the house.

Discover more from This Quirky Life

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

love the stepping back in time… just fab!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It was a wonderful experience but am glad I never had to wear a corset!

LikeLike