A colleague recently travelled with his family to the Kimberley in Western Australia (WA), hiking in the remote bush. Hearing of his tales and seeing the photos reminded me of my travels and adventures in WA in 2003, and prompted me to dig out my photo album*. The characters I met were as colourful as the sea- and landscapes I explored. *please excuse the grainy photos photographed from said album.

On a mature gap year in Australia – my house in Oxford rented out – I had been staying with friends of friends in Freemantle, a suburb of Perth, camping in their garden. A bit less Princess and the Pea than I am now, I shared the tent with a littler of Jack Russell puppies for company. I’d wake up with the puppies snuggled in my armpit, across my belly and around my head. How I adored them, particularly one of them whom I named Oscar.

From Perth I travelled north up to Exmouth with Australian Adventure Tours. The tour included sandboarding in Geraldton, marvelling at the Pinnacles, ancient limestones formations – some rather phallic-looking – as our guide Colin was (very) quick to point out, hanging out with bottlenose dolphins at Monkey Mia in the Shark Bay World Heritage Area and learning about the nearby Hamelin Pool stromatolites, layered sedimentary rock formations, single-celled organisms, that produce oxygen in a saltwater environment and were once the dominant lifeforce on earth! We passed through Carnarvon (my diary reading simply: Boiling! Banana plantations, NASA dish, supermarket and, according to Colin, the cheapest grog till Broome), swam with the whale sharks at Coral Bay, a wonderfully life-affirming – and energetic – experience, drank in orangey-red dawn and dusk skies and travelled on red dust dirt roads.

We stayed at various old homesteads and stations including Warroora Station (meaning Woman’s Place in the local Aboriginal language), where we made raisin damper, sat round the campfire, and where I did my best to keep Colin at bay. I was the odd number on the tour; our party consisted of two gay girls from Tasmania, two rather inflexible German girls (they eschewed the damper at breakfast saying: “nein danke, only ever muesli in the morning”) and two sweet and giggly Japanese girls.

Colin was unapologetically Colin endlessly searching beaches for ‘Eye Candy’ and regaling us with apocryphal stories of past conquests such as Debbie from Essex. He was sweet on me, insisting I sit next to him in the front of the van and dropping inuendo-laden hints, but I came away unscathed bar some campfire hugs. While he was a bit of a tour guide cliché, he created camaraderie, kept us all entertained and energised and loved his job.

My next stop was the Ningaloo Reef Retreat (before it got upmarket and swanky). Ranger Dave with his bright eyes and rasta blond hair took out us to the turtle beds and kayaking on the Blue Lagoon. Sadly, even then, more than 20 years ago, there were sections of dead coral but what I remember more is the extraordinary diversity of marine life, the dazzling colours and quirky names of the fish. To name a few, we saw sailfin catfish, the harlequin snake eel, Tawny nurse sharks, Christmas Tree worms, fusiliers, humbugs, sweetlips and convict surgeon fish being chased by black damsels. A very different vibe from Colin’s tour, Dave was more Hippie Hippie Shake and exuded the kind of positive energy that comes from living close to nature. I also enjoyed the company of Mike, a curator of Indigenous art, a chain smoker of roll-ups with gappy teeth and wild and woolly grey-blond hair, and his wife Ilse, a linguist.

From Ningaloo Reef I took the overnight bus to Karratha, a mining town, to join a tour to the Karijini National Park. Due to arrive at 6.30 am, I had booked into a backpacker’s, and, as arranged, the manager came to meet me at the service station. I had stayed in some wonderful youth hostels in the south of WA – at Denmark, at Bunbury and Albany. Here, my room overlooked a courtyard full of cigarette stubs and empty beer cans, there were ants, chicken bones and food on the floor in the kitchen, and I’ll spare you the detail of the bathrooms. Tired from a night on the bus, I couldn’t handle the nicotine-imbued squalor. Looking back, I realise this place was a budget option for mine workers and transient labourers rather than travellers.

The manager was furious when I complained it was dirty. She screamed at me, blaming me for getting her out of bed at 6 am and flung $30 of the $50 I had paid into my hand and booted me out the door. In today’s parlance, we’d say I’d been cancelled! Smarting from the experience, I cut a tragic figure wheeling my case along the streets looking for alternative accommodation. But all was well as I pitched up at the Mercure and for $98 (bargain!) got a sparklingly clean room, TV, air-con, private bathroom and access to the pool. Bliss.

At 7.30 am the next morning, Andrew from Snappy Gum Safaris picked me up for the tour I’d booked to the Karijini National Park. We had to wait around a bit as his brother Brendan was still in the shower and nursing a hangover and sore leg from coming off his motorbike the night before. Something about the camber of the road. Yeah, right… And guess what? I was the only one on the tour, a fact which came back to haunt me.

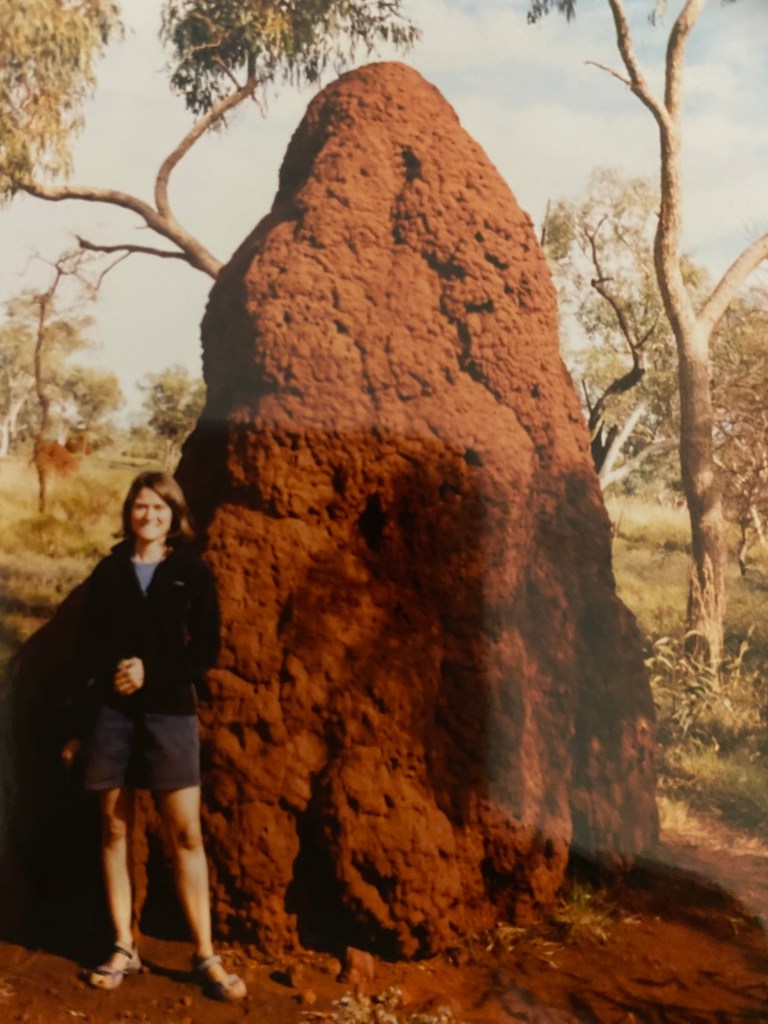

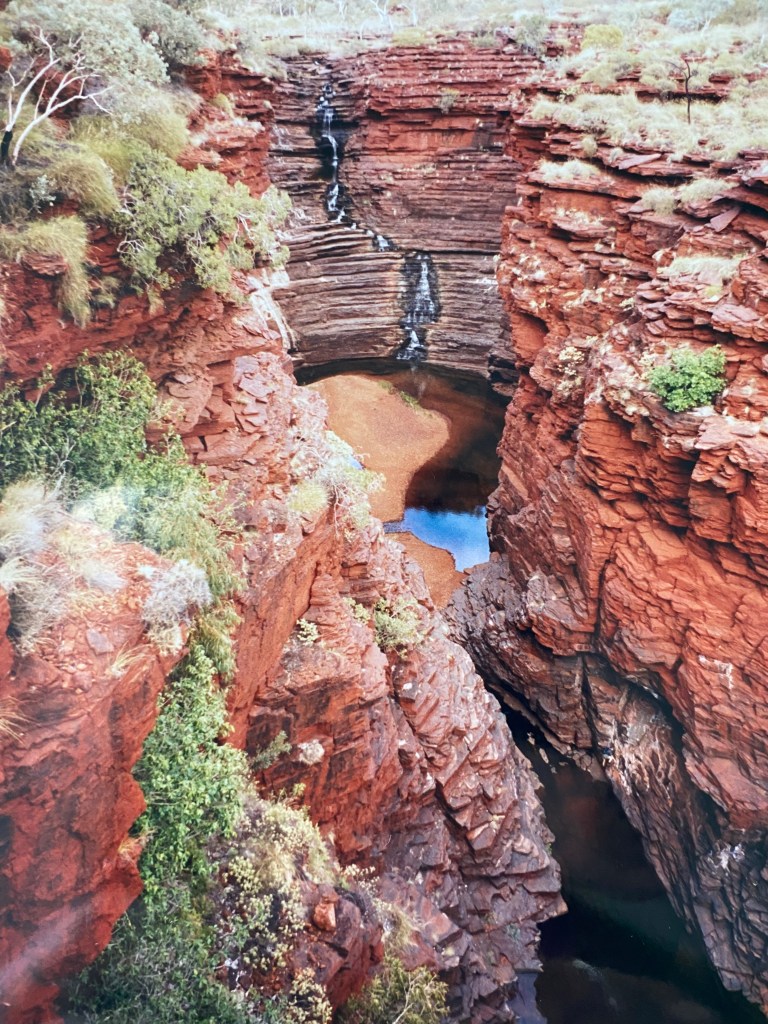

Karijini is iron ore country. It is vast, remote and characterised by rust red dirt roads, cliffs, gorges and large termite mounds interspersed with splashes of green ranging from the grey green of the gum trees and the spinifex grass to the brilliant jade of the water in the rock pools. It’s like being inside a Fred Williams painting.

It’s a four-to-five-hour drive and, with a few stops along the way – a deserted homestead and a spidery drop dunny – we got to our first stop at lunchtime, the Hamersley Gorge, where Brendan and I had a dip in a water hole, the waterfall giving our shoulders a gentle massage. Sounds good doesn’t it but the brothers were distant and disengaged, cross that they were not making any money by taking one person on the tour. While there was no male/female tension, they were keen to get their pound of flesh.

By early evening we crossed the dry riverbed of the Fortescue River towards the Rio Tinto Gorge (note how the big mining companies have claimed and named the land as theirs) and the Dales Gorge camp site, which was just a patch of red earth. Here they set up our swags and, for mine, hitched up a mosquito net to a tree branch.

Dinner was cheap sausages cooked over a fire served with salad and, to drink, bog standard cask wine or Victoria Bitter (VB). My diary reports the boys ‘romped through the VB’ and complained about penny-pinching backpackers. I was almost starting to miss cuddly Colin.

By chance a group of four tourists – an English girl, a Dutch girl and two Canadian blokes – came over after dinner and asked Andrew and Brendan if they knew the park and the various hikes. They boys went into a huddle with them while I sipped at my wine. Dollar signs in their eyes, they turned back to me after about ten minutes and asked how I’d feel about changing the itinerary to walk the much-more-exciting Miracle Mile the next day? It’d be the walk of a lifetime, the said. The tourists were keen to engage them as guides. Ching Ching.

Miracle Mile, why not? It sounded good and I didn’t want to be the party pooper. I slept reasonably well in my swag – apart from being startled awake by one of the boys shouting in his beer-soaked sleep, after which I got a bit lost going for a pee in the spinifex. No mobile phone torches in those days!

After a light breakfast, the day started gently with a trip to the Joffrey Falls, Knox Gorge lookout and Oxers lookout which is the meeting point of four gorges.

And then the adventure started. No wonder they had stuck to the catchy Miracle Mile moniker rather than detailing what it involves. The Miracle Mile is within the Hancock Gorge and the Joffre Gorge and involves walking along extremely narrow 20-metre gorge walls. While we did have helmets, there was no rope, and one wrong foot could have spelled disaster.

It was physically and mentally demanding, but what made it most challenging for me was being the odd one out while the other four were a bonded team, walking together and encouraging each other on. I’ve always loved a bit of solitude and peace and quiet, but this was uninvited exile. I changed schools a lot as a child, and this reminded me of being the new girl and not having a gang to belong to.

At one point I slipped and grazed my knee, irritating Andrew, who was walking behind me. Shaking, I picked myself up and pushed on, desperate not to let the others see my fear – and suppressed fury! We crawled, climbed, clambered and inched our way along, in parts spreadeagled between gorge walls, jumping into rock pools below and swimming between gorges, floating our day packs on air beds. Andrew and Brendan set challenges and dares for the others, while I waited around – like a spare part at a wedding – getting cold (think damp bathers in shaded gorges), tired and hungry. When I got back to the car at the end, I bit into an apple only to crack a tooth!

The scenery was out of this world SPECTACULAR but I’m appreciating it more all these years later looking back at the photos in my album. My diary description from 11 May 2003 is underwhelming: Fab gorges, layering and rocks but wasn’t happy in my head as Phil (an ex) would say. It was a tough character-forming experience, but one I will never forget. And as my German teachers would say: it’s all grist to the mill. Indeed, and 22 years on it makes a good story for my blog!

He laments the amount of waste (including wrecked and rusting cars) in American cities, and the amount of packaging used in every day life: “I do wonder whether there will come a time when we can no longer afford our wastefulness – chemical wastes in the rivers, metal wastes everywhere, and atomic wastes buried deep in the earth or sunk in the sea.” He talks of towns encroaching on villages and the countryside, supermarkets edging out ‘cracker-barrel’ stores. “The new American finds his challenge and his love in traffic-choked streets, skies nested in smog, choking with the acids of industry.” And he encounters political apathy – life seems to revolve more around baseball and hunting than discussions about the respective merits of Kennedy versus Nixon in an election year. Sound familiar?

He laments the amount of waste (including wrecked and rusting cars) in American cities, and the amount of packaging used in every day life: “I do wonder whether there will come a time when we can no longer afford our wastefulness – chemical wastes in the rivers, metal wastes everywhere, and atomic wastes buried deep in the earth or sunk in the sea.” He talks of towns encroaching on villages and the countryside, supermarkets edging out ‘cracker-barrel’ stores. “The new American finds his challenge and his love in traffic-choked streets, skies nested in smog, choking with the acids of industry.” And he encounters political apathy – life seems to revolve more around baseball and hunting than discussions about the respective merits of Kennedy versus Nixon in an election year. Sound familiar?

Later in the trip we travelled by overnight train in a sleeper compartment from La Coruña to Madrid. We’d come straight from the beach and our bikini bottoms were still gritty with sand. A man with a dark five o’clock shadow and reeking of garlic came into our compartment early in the night and claimed the third of four bunks. After a few station stops where, each time, travellers would slide open the door to our compartment in search of a bed, garlic man got up, swearing a very Spanish joder (Google it!) and locked the door. Terrified as to his motives, we whispered frantic contingency plans, but soon realised that he simply wanted to get a good night’s sleep without disturbance. Selfish maybe, but not a sexual deviant, his swearing was replaced by snores. No joder simply a bit of roncar!

Later in the trip we travelled by overnight train in a sleeper compartment from La Coruña to Madrid. We’d come straight from the beach and our bikini bottoms were still gritty with sand. A man with a dark five o’clock shadow and reeking of garlic came into our compartment early in the night and claimed the third of four bunks. After a few station stops where, each time, travellers would slide open the door to our compartment in search of a bed, garlic man got up, swearing a very Spanish joder (Google it!) and locked the door. Terrified as to his motives, we whispered frantic contingency plans, but soon realised that he simply wanted to get a good night’s sleep without disturbance. Selfish maybe, but not a sexual deviant, his swearing was replaced by snores. No joder simply a bit of roncar!