Over the winter friends and family have shared northern hemisphere holidays photos – lots of wish-you-were-here vibes. There’ve been pictures of sardines grilling in Southern Spain, Gothic churches in Germany, flower-lined canals in Utrecht, dazzling white-washed vistas in Santorini, yodel-inducing Swiss alpine scenes, lush green coastal paths in Devon, quirky markets and Lord’s Cricket Ground in London and windswept beaches at the northernmost tip of Denmark.

I’ve enjoyed looking at the pictures and have imagining myself there in mind and body, but I haven’t felt an ounce of envy. I’ve been just fine and dandy staying put in Melbourne. The Melbourne winter can bite, especially the wind, but it’s mild compared to a UK winter. Although I feel the cold, there’s nothing more energising than a rain- and wind-lashed walk on the beach with the dog children – Rupert, the dachsie, my canine nephew, has ‘over-wintered’ with me and Bertie.

I enjoy the seasonal variation – summer can be very intense requiring a lot of sunscreen slip, slop, slap – and finding warmth in soups, stews, candles, hot baths and snuggling with the dogs on the sofa. There are grey days in the mix which make me feel right at home but there are also some glorious sunny days in the high teens, when there’s no better place to hang out than in my courtyard garden.

Immersing myself in artsy things has provided another form of nourishment these last few months. One of the zanier exhibitions my friend Kaliopi and I went to was Swingers – The Art of Mini Golf. I had no idea that mini golf had its origins in feminism. In the 19th Century a group of Scottish women, rebelling at being told that swinging a golf stick was unladylike, commissioned a 9-hole putting-only course which became known as the Himalayas due to the uneven terrain. The course still exists today, alongside St Andrews Golf Course near Edinburgh.

Swingers is an interactive exhibition staged in the former Victorian Rail Institute ballroom upstairs at Flinders Street Station. We navigated the nine-hole golf course created by nine female and gender-diverse artists. My favourite was the first hole, a big, bold and colourful desert scene by Yankunytjatjaraartist Kaylene Whiskey, complete with Greyhound bus and featuring Cathy Freeman and Dolly Parton. Putting is harder than it looks – you’re never going to get me playing golf – but we navigated the course as best we could.

Other works included videos of the Teletubbies, an eerie Carnival Clown face, spooky scenes reminiscent of the Mexican Day of the Dead and, at one of the holes, we had to attach a latex animal tail and swing it with our bodies to putt the ball. Well, what can I say, maybe if you’re as flexible as a hula hoop dancer… Much hilarity ensued but it did nothing for our technique.

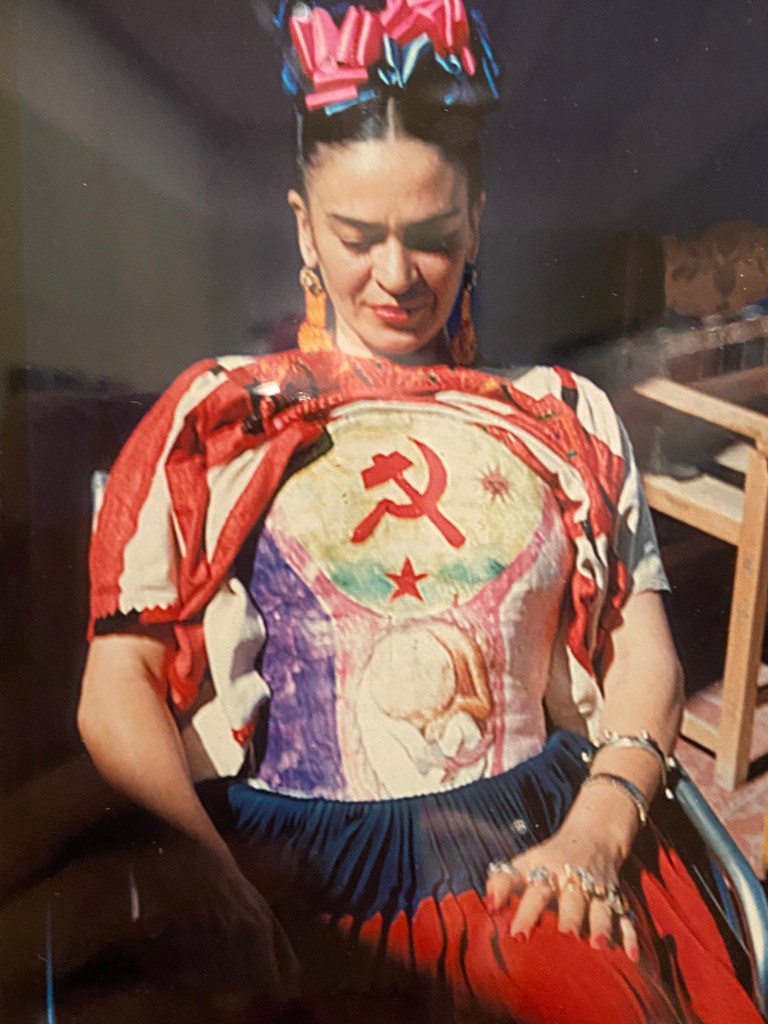

Another big pop of colour came courtesy of another feminist – in July I went up to Bendigo in regional Victoria to see Frida Kahlo: in her own image. As well as her paintings, self-portraits and the fabulous costumes, jewellery and flowers that she wore are some of her personal items that were sealed in a bathroom for 50 years after her death. These include lipsticks, powder compacts, medicines and herbal tinctures. As well as polio aged six, she suffered a horrendous accident in 1925 leading to life-long injuries when a streetcar collided with the bus she was travelling in. During her recovery she began to paint and used mirrors and an easel positioned over her bed. She underwent multiple surgical interventions, lived with chronic pain and had to wear a corset every day from 1944.

What shines through is her resilience, her deep love of animals and the natural world, her courage not only to channel her pain and disability into art but her readiness to challenge the prevailing societal and political norms. She was the daughter of a German/Hungarian father and a Mexican mestiza mother and, rather than follow the European-influenced fashions of the time, she honoured her Indigenous heritage and wore the traditional blouses, skirts and shawls from the Tehuantepec Isthmus, a matriarchal society. And although her life was cut short by gangrene in 1953, she lived to the full. She and Diego Rivera had an up and down marriage, they both had affairs – Frida even had a brief affair with Leon Trotsky. She was a member of the Mexican Communist party and painted one of her plaster corsets with a hammer and sickle.

Continuing with all things Hispanic, and following my March trip to Malaga, I saw five exquisite films at the Spanish Film Festival and luxuriated in the cadence and rhythms of the language. My two favourites were Wolfgang, a warm-hearted comedy about a nine-year-old highly intelligent boy with autism spectrum disorder, who re-establishes a relationship with his father following the death of his mother. And Ocho, a love story set across eight decades and eight defining moments in Spain’s history including the Civil War which split friends and families apart. A masterful and magical movie from the 2025 Malaga Film Festival.

A creole mass – Missa Criolla by Argentinian Ariel Ramirez – in a city church was a revelation. In place of the traditional Latin Mass, this was a folksy mass featuring dance, instrumental and song forms from Argentina blending Indigenous, African and European influences. The concert included other gems ranging from Spanish classical guitar pieces and a Peruvian hymn in the Quechua language to an Afro-Brazilian chant by Villa-Lobos, and Libertango, a piece composed by Argentinian tango composer Piazzolla. You’ll likely know the famous instrumental version, but we heard the choral adaption by Oscar Escalada with voices playing the parts of instruments.

I came out of the concert with an Andean beat pulsing in my veins, the maracas sounding in my ears and added South America to my travel wish list. There’s been a strong Hispanic thread this winter. A few months ago, I went to a jazz club in north Melbourne to hear the Brazjaz Ensemble headed up by Carlos Ferreira, a Samba specialist from Rio de Janeiro. It was the real deal – mellow, moody and intense – and the newly graduated (2022) flautist, Yael Zamir, gave an extraordinary performance. The set included about five songs, two of which I recognised from a CD I used to play in my London days in the 90s.

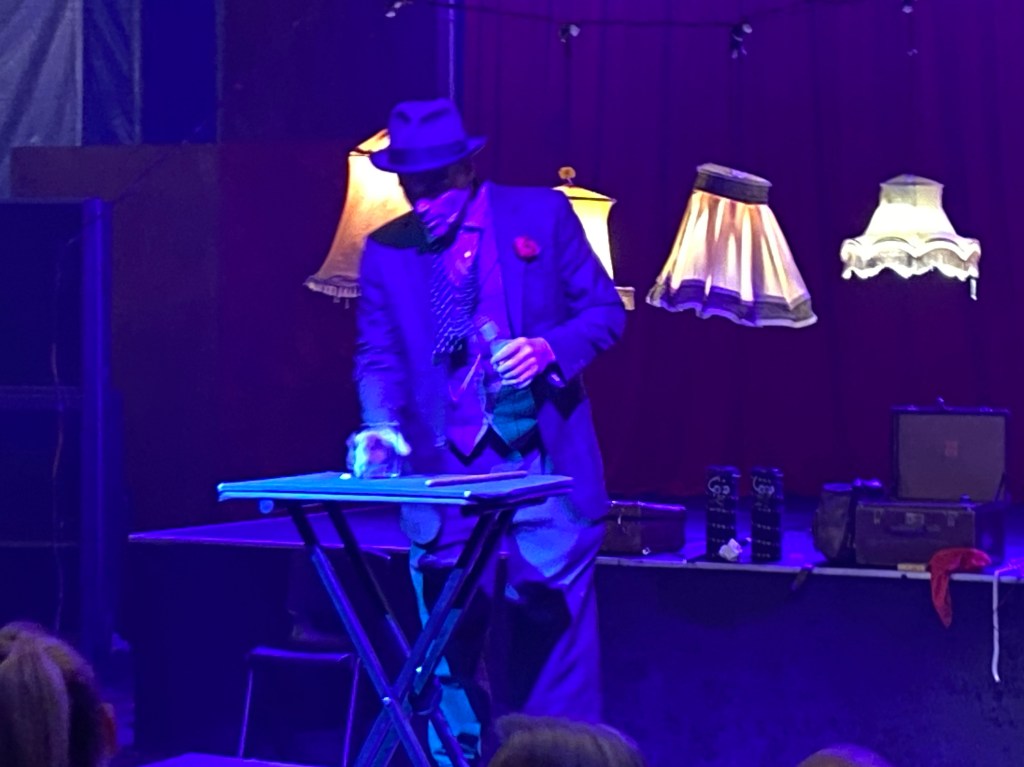

I’m a big fan of escapist musicals – it’s easier than meditation – that transport me to a make-believe world. Beetlejuice with Eddie Perfect was no exception. It’s a dark comedy about ghosts, zombies, life and death with a great score including a couple of Harry Belafonte favourites – Day-O and Shake Senora.

I went with my friend Angela and her daughter Alice, and we indulged in a Beetlejuice-themed high tea beforehand which included ghoulish lime green cocktail, black and white sugar snakes, dark chocolate and pepper scones, shrunken head tarte and a smoking concoction that added to the mystique.

This Sunday, I celebrated the last day of winter by going up to Kyneton to see Alice – a rising star – perform in Mary Poppins with Sprout Theatre, a youth musical company in the Macedon Ranges. A wonderfully high energy production performed by a cast of talented young people ranging from tiny tots in the junior class to teenagers in the senior classes. Beautifully staged and choreographed, it was a knockout with great singing and dancing including coordinated moves and can-can kicks that must have taken a fair bit of rehearsing. As a two left feet person, I was impressed. Absolutely supercalifragilisticexpialidocious!

Mary Poppins is one of my all-time favourite musicals, and its story and messages are as relevant today as they ever were; family is more important than work and money, find the silver linings and positives “Just a spoonful of sugar”, and believe in the power of creativity and imagination: “Anything can happen if you let it.” Sound advice!

He laments the amount of waste (including wrecked and rusting cars) in American cities, and the amount of packaging used in every day life: “I do wonder whether there will come a time when we can no longer afford our wastefulness – chemical wastes in the rivers, metal wastes everywhere, and atomic wastes buried deep in the earth or sunk in the sea.” He talks of towns encroaching on villages and the countryside, supermarkets edging out ‘cracker-barrel’ stores. “The new American finds his challenge and his love in traffic-choked streets, skies nested in smog, choking with the acids of industry.” And he encounters political apathy – life seems to revolve more around baseball and hunting than discussions about the respective merits of Kennedy versus Nixon in an election year. Sound familiar?

He laments the amount of waste (including wrecked and rusting cars) in American cities, and the amount of packaging used in every day life: “I do wonder whether there will come a time when we can no longer afford our wastefulness – chemical wastes in the rivers, metal wastes everywhere, and atomic wastes buried deep in the earth or sunk in the sea.” He talks of towns encroaching on villages and the countryside, supermarkets edging out ‘cracker-barrel’ stores. “The new American finds his challenge and his love in traffic-choked streets, skies nested in smog, choking with the acids of industry.” And he encounters political apathy – life seems to revolve more around baseball and hunting than discussions about the respective merits of Kennedy versus Nixon in an election year. Sound familiar?